Blood- and noir-stained

On Sunday evening, my viewing companion and I saw, as part of the American Cinematheque's continuing tribute to classic British horror, Jacques Tourneur's Curse of the Demon aka Night of the Demon (1957). We actually saw the British version (Night), which includes approximately 10 minutes of footage originally excised from the stateside version. (The currently available DVD includes both cuts of the film.)

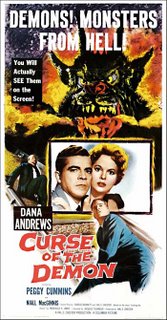

Demon follows the trip of an American psychologist, John Holden (Dana Andrews), to a conference in England, where, along with a comely, more open-minded schoolteacher, Joanna Harrington (Peggy Cummins), he is drawn into an investigation of the mysterious circumstances surrounding the death of Dr. Harrington, a professor who had been Holden's colleague and Joanna's uncle. Dr. Harrington had sought to debunk the theories of the local occultist, Julian Karswell (Niall MacGinnis), and ultimately expose him as a fraud and criminal. As a man of unimpeachable science and rationality, Dr. Holden shares the objectives of his dead friend, and in his quest to apply a logical explanation to the strange occurrences in and around London, he confronts Karswell, who in turn confronts the man of science with a dark, unsettling truth.

One of Demon's treasures is its characterization of this suspected dabbler in the dark arts. Karswell simultaneously plays the part of good citizen and Devil's minion. This soft-spoken, portly, balding

man demonstrates his largesse by inviting the local children to his sprawling estate for a Halloween party featuring ice cream and a magic show performed by Karswell himself in full hobo clown regalia. And yet, in addition to making casual threats, this curious fellow exhibits other traits of unambiguous, old-movie evil. He has a satanic little beard (not quite a Vandyke), dyed jet black. Moreover, although his live-in mother is not at all domineering, the bachelor Karswell is nonetheless a "fussy" (her word) mama's boy, if you catch my drift. In any event, Karswell is much more engaging than Holden, the skeptical, ostensible hero of our fable. I, for one, kept waiting for the genial demonologist to bring a rain of hellfire down on Mr. Scientist's smug, unbelieving ass.

man demonstrates his largesse by inviting the local children to his sprawling estate for a Halloween party featuring ice cream and a magic show performed by Karswell himself in full hobo clown regalia. And yet, in addition to making casual threats, this curious fellow exhibits other traits of unambiguous, old-movie evil. He has a satanic little beard (not quite a Vandyke), dyed jet black. Moreover, although his live-in mother is not at all domineering, the bachelor Karswell is nonetheless a "fussy" (her word) mama's boy, if you catch my drift. In any event, Karswell is much more engaging than Holden, the skeptical, ostensible hero of our fable. I, for one, kept waiting for the genial demonologist to bring a rain of hellfire down on Mr. Scientist's smug, unbelieving ass.Demon entails far too much to fully catalogue here, including a séance, catatonia, hypnosis, electrocution, a children's-party windstorm, creepy rural-Gothic townsfolk, intensive library research, a vicious stuffed-animal jaguar attack and, yes, the titular demon. The demon's mercifully limited appearances are the only moments marring the film's real triumph: its rich visual presentation. (Most commentators speculate that the shots of the demon were included against Tourneur's wishes, an interpretation substantiated by the director in later interviews. I don't particularly mind the distant, full-length views, showing the marauding beast's approach.

In close-ups of its visage, however, it appears more temperamental real-world animal than terrifying emissary of Hell. But it's easy to grasp the commercial rationale for this less subtle approach when at least one of the film's posters screams "Demons! Monsters from Hell!" and hyperbolically promises "You will actually SEE them on the screen!" No coonskin cap-wearing patron wanted to feel "gypped" after all. My own friend, too, has a soft spot for this creature, but her soul was consigned to Hell long ago.) Considering he's working in black and white, Tourneur has an amazingly extensive palette at his disposal. He soaks the proceedings in dread, alternating subtle and stark shadings to depict less an interplay of light and shadow than an age-old battle between the two, one in which the insidious darkness has gained a distinct advantage. Tourneur cut his teeth on projects like the Val Lewton-produced Cat People (1942), another moody horror entry that opts for suggestion over shock and obviousness.

In close-ups of its visage, however, it appears more temperamental real-world animal than terrifying emissary of Hell. But it's easy to grasp the commercial rationale for this less subtle approach when at least one of the film's posters screams "Demons! Monsters from Hell!" and hyperbolically promises "You will actually SEE them on the screen!" No coonskin cap-wearing patron wanted to feel "gypped" after all. My own friend, too, has a soft spot for this creature, but her soul was consigned to Hell long ago.) Considering he's working in black and white, Tourneur has an amazingly extensive palette at his disposal. He soaks the proceedings in dread, alternating subtle and stark shadings to depict less an interplay of light and shadow than an age-old battle between the two, one in which the insidious darkness has gained a distinct advantage. Tourneur cut his teeth on projects like the Val Lewton-produced Cat People (1942), another moody horror entry that opts for suggestion over shock and obviousness.Throughout Demon, I was struck by how much it looked like a canonical film noir, as dark, pristine and elegant as Tourneur's own Out of the Past (1947). Demon's noir credentials, as it were, extend to its leads, Andrews, who starred in Laura, another classic (and classical) noir, and Cummins, the femme fatale of the B-movie thrill ride, Gun Crazy (aka Deadly is the Female). I was again reminded that, by their existence, certain films toy with that loose conceptual thread, threatening to pull the entire noir classification asunder. Is it noir? Is it horror? Does it matter? In addition to its explicit supernatural elements, Demon diverges from noir in its comparatively unshaded depiction of good and evil as embodied, respectively, by Holden and Karswell. But in the film's still noirish (and Biblical) universe, knowledge comes at the price of innocence. Victory feels like loss. The horror genre, including Expressionist nightmares and Hollywood monster movies, had informed noir, providing stylistic and thematic cues. With Curse of the Demon, noir returned the favor.

2 Comments:

Thank you, Norman. Excellent analysis, as always.

Well done! Sorry to have missed the Demon.

Post a Comment

<< Home